Sometime last year, a close cousin was battling with cancer. From his home town, he would come to our house to get chemo sessions done in the nearby hospital. I would feel sorry for him, his suffering and that of his wife, as they spent weeks away from their two daughters, fighting the deadly battle. At that moment, no one was thinking that he wouldn’t make it back. Physically, he was tall, well-built, had a great sense of humor (told me spooky stories even after his chemo sessions) and was trying to conduct business as usual. Nothing about him, his appearance, his personality, hinted that his fire could be diminished.

And then, the day came when we were asked to see him, probably the last time. As I looked at that emaciated body, drained of all the life I had celebrated in him, I shook to the core. He had literally wilted away. It wasn’t him at all.

Soon, one morning. A WhatsApp message on the family group came up. We had lost him. I saw flashes of all the times we had spent together. His jokes, that smile, him getting surprised by how many chapatis I eat (I don’t eat a lot). And when I turned the age exactly ten years younger than what he was, I thought. Did he know? When he was celebrating his 32nd birthday, did he know that he only had a decade to live? That he would go from this world in ten years. And if he did, what would he have done differently?

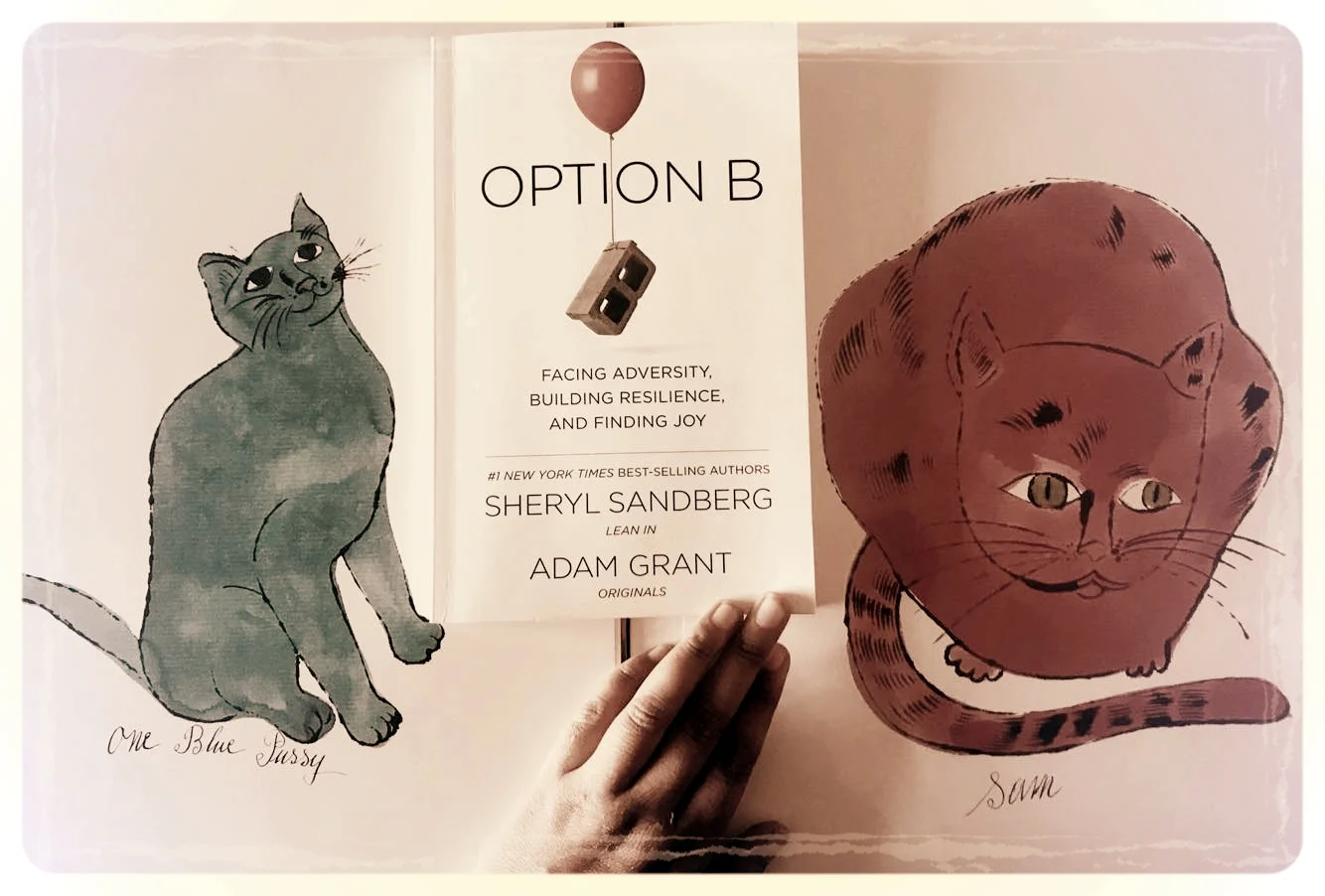

Sheryl Sandberg didn’t lose her husband to a debilitating illness for two years. But that would have made her suffering more painful. Finding your husband dead in a resort gym where you’ve gone for a celebration is a view I wouldn’t wish on even the most wretched being on the planet.

From that last year, fighting an illness myself, I found myself crawling into a tunnel, blindfolded, writhing in pain I had never experienced, seeing my husband anxious, confused and terrified of seeing me in that situation. And then, as I started talking to more people around me, I found myself redefining what a normal life looked like. Almost everyone shared their stories of fighting through pain, of dealing with death, of illnesses that they were occupied with, of insecurities that held them back and from childhoods that weren’t fair on them.

And reading through this book, as it offered wisdom upon wisdom of building resilience as a muscle, the one thread that kept the narrative held together was the normalisation of suffering — if I went through life assuming that suffering was something that happened to other people, as an accident. Then, I would always go through life grumpy, in denial and in shock of the unusual accident. But if I understood life as one of suffering, I would be kinder to myself, kinder and more empathetic to others, would work to minimise the damage of life’s vicissitudes to others. In other terms, I would be wary of surfing and chasing local maxima.

if I understood life as one of suffering, I would be kinder to myself, kinder and more empathetic to others, would work to minimise the damage of life’s vicissitudes to others. In other terms, I would be wary of surfing and chasing local maxima.

Normalising suffering though can’t happen with everyone. We can’t really say that to young kids who are suffering abuse, torture or are in physically dangerous situations, to rape survivors, to people struck with crushing poverty and illiteracy, to millions of people who genuinely don’t get a decent shot at a good life.

That’s why, I thought this book was important. To people who have the blessings of the randomiser (I am an atheist), who can look beyond the immediate suffering to understand it thoroughly, they must understand it like we understand fever, our muscles, headaches and obesity.

From the book, I am sharing some non-intuitive research results that shocked, gave me hope for dealing with adversity and some, a bit of sunshine.

- When you are faced with adversity/setback, these three feelings will hinder your recovery

Psychologist Martin Seligman found the three P’s that will stunt recovery.

- personalisation — the belief that we are at fault

- pervasiveness — the belief that an event will affect all areas of our life

- permanence — the belief that the aftershocks of the event will last forever

- People tend to avoid discussing upsetting topics. A phenomenon so common, it even has a name — mum effect — for when people avoid sharing bad news

This silence is crippling for people who are suffering. If you know your colleague had a death in the family, is suffering through a mental health issue and you chose to keep mum about it, you are isolating that person and their suffering. Your avoiding to discuss that issue won’t do any good.

Grief is a whisper in the world and a clamor within. More than sex, more than faith, even more than its usher death, grief is unspoken, publicly ignored except for those moments at the funeral that are over too quickly. – Anna Quindlen

- When people are in pain, they need an escape button — they might not use it, but it is comforting just by being there.

In studies of impact of stress, people performed tasks that required concentration, like solving puzzles while being blasted at random intervals with uncomfortably loud sounds. They started sweating and their heart rates and blood pressure climbed. They struggled to focus and made mistakes. Many gave up. And then, researchers gave some of the participants a way out.

If the noise became too unpleasant, they could press a button and make it stop. The button allowed people to stay calmer, make fewer mistakes, and show less irritation. But you know what was surprising?

None of the people actually pressed the button. Stopping the noise didn’t make the difference, knowing they could stop the noise did. The button gave them a sense of control and allowed them to endure the stress.

Adam Grant uses this by writing his cell phone number on the board on the first day of his undergraduate class. He lets his students know that if they need him, they can call at any hour. Students use this number infrequently, but along with the mental health resources available on campus, this gives them each an extra button.

- If you are in trauma, in pain — journal

Jamie Pennebaker had two groups of students journal for fifteen minutes a day for just four days — some about nonemotional topics and others about the most traumatic experiences of their lives – including rape, attempted suicide, and child abuse. After the first day of writing, the second group was less happy and had higher blood pressure. This made sense, since confronting trauma is painful. But when Pennebaker followed up six months later, the effects reversed and those who wrote about their traumas were significantly better off emotionally and physically.

Writing about traumatic events can reduce anxiety, anger, boost your grades, reduce absences from work, and lessen the emotional impact of job loss. Health benefits include higher T-cell counts, better liver function, and stronger antibody responses.

- Labeling negative emotions can help us process them, labeling positive emotions works as well!

Writing about joyful experiences for just three days can improve people’s moods and decrease their visits to health centres a full three months later. We can savor the smallest of daily events — how good a warm breeze feels or how delicious french fries taste.

Thanks Sheryl and Adam for choosing to use your adversity into a learning ground for so many others.